Non-ammocoete larvae of Palaeozoic stem lampreys

– Fossilized fish larvae overturn long accepted scenario of vertebrate origin –

Tetsuto Miyashita, Robert W. Gess, Kristen Tietjen & Michael I. Coates. (2021).

Also see my guest post in Nature Ecology & Evolution Community:

"Agnatha All Along? Changing the Evolutionary Narrative on Vertebrate Origins"

Growth series of Priscomyzon, a stem lamprey from the Late Devonian of South Africa

Reconstruction of a hatchling individual of Priscomyzon (Illustration by Kristen Tietjen)

Summary

Since the 19th century, biologists have treated the larvae of lampreys (jawless eel-like fish) as a relic of deep evolutionary ancestry. These blind, filter-feeding, worm-like larvae (ammocoetes) grow into blood sucking adults with a circular mouth lined with horny teeth. Crucially, this strange life history was thought to echo transformations some 500 million years ago which give rise to all fish lineages, including the one that ultimately led to ourselves.

However, new fossil discoveries contradict the conventional wisdom that our long chain of ancestors ever included a lamprey-like fish. These fossils, belonging to four extinct lamprey species, were discovered in South Africa and the United States and range from 310 to 360 million years old. Different stages of lamprey life cycles are preserved, allowing paleontologists to track their growth from hatchling to adult. Remarkably, the smallest individuals, barely 14mm in length (fingernail sized), still carried a yolk sac, signaling that these had only just hatched before entering the fossil record. But further examination revealed that these neonates were already sighted with large eyes and armed with a toothed sucker, much like the blood-sucking adult phase of modern lampreys and completely unlike their modern larval counterparts.

This drastically different life cycle of ancient lampreys provides the evidence that modern lamprey larvae are not evolutionary relics. Rather, these modern filter-feeders are a more recent innovation that allowed lampreys to populate and thrive in rivers and lakes. Vertebrate ancestry, instead, descends from extinct armored fish without ever taking a detour through a larval lamprey-like phase.

Graphic summary

Traditional view

Ammocoete, a filter-feeding larval form of a modern lamprey, was believed as an evolutionary relic of – and therefore a proxy for – the common ancestor from which all vertebrate lineages descended.

Image credits – Modern lamprey, adult: US Geological Survey; Modern lamprey, larva: Gregory Kovalchuk; Fossil lamprey (Priscomyzon): Kristen Tietjen; Ostracoderm (Arandaspis): Franz Anthony

New view

The discovery of a new larval form in fossil lampreys now provides evidence that an ammocoete is a more recent adaptation. Unlike the blind, filter-feeding ammocoete, ancient larval lampreys had large eyes and a toothed sucker. Instead, armoured jawless vertebrate called ostracoderms are closer to the vertebrate ancestor. This new view of vertebrate ancestry suggests that the first vertebrates already had bones in their skeleton, and the development of modern lampreys offers little direct insight to the ancestral condition of vertebrates.

Why Is This Significant?

Biologists have long assumed a larval form of modern lampreys (ammocoetes) to retain features of the ancestor of all living vertebrates (fish and four-legged animals). This conventional wisdom is now overturned by the discovery of non-ammocoete larvae in ancient lampreys. Now we have to think differently about the deep ancestry of our own lineage.

The blind, filter-feeding ammocoete larva of a Pacific lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus).

Photograph by Gregory Kovalchuk

Team

Top row, L-R: Tetsuto Miyashita (Canadian Museum of Nature), Robert W. Gess (Albany Museum)

Bottom row, L-R: Kristen Tietjen (University of Kansas), Michael I. Coates (University of Chicago)

— Background —

- Lampreys are blood-sucking parasitic fish (underwater vampires, if you will) that do not have jaws or a bony skeleton.

- Lampreys begin their life as a blind, sand-burrowing, worm-like form that slurps up the water for tiny food particles. This stage is called an ammocoete.

Life cycle of a modern lamprey (Image credit: US Geological Survey)

- Ammocoetes have been believed since the 19th century to retain the ancestral form that gave rise to all vertebrate animals (including humans).

- However, the fossil record had little to say as to whether or not the ammocoete form existed in primitive lampreys.

- If ancient lampreys had an ammocoete stage, then the textbooks would be correct all along: modern lampreys go through this ancestral stage during their growth (=we can still see the image of our ancestor in ammocoetes).

- If modern lampreys came from ancestors that did NOT have an ammocoete stage, however, the ammocoete is then an evolutionary innovation, not an evolutionary relic.

The life of a modern lamprey

Ammocoete larva

Lamprey adult

LAMPREY from Hakai Magazine on Vimeo.

https://hakaimagazine.com/

In this three-minute video, Aaron Jackson of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation explains how the plight of the Pacific lamprey impacts his community and the steps tribes are taking to restore the fish for future generations. Footage adapted from the film The Lost Fish ©Freshwaters Illustrated thelostfish.org

— Highlights from the paper —

- A team of paleontologistsreported fossilized remains of larval lampreys from 360 to 310 million years ago in South Africa and the United States.

- The fossils belong to four extinct lamprey species: Priscomyzon riniensis from the Devonian period of South Africa; Mayomyzon pieckoensis, Pipiscius zangerli, and Hardistiella montanensis, all from the Carbonifeous period of the United States. They all represent early branches of the lamprey lineage.

- The fossilized larvae range from hatchling (carrying a yolk sac; fossilized soon after hatching out of an egg) to subadult and form a series so paleontologists can track changes in their anatomy during growth. Hatchlings were identified for Priscomyzon and Pipiscius, indicating that the fossil localities record environments that were both hatchery and nursery for the early lampreys.

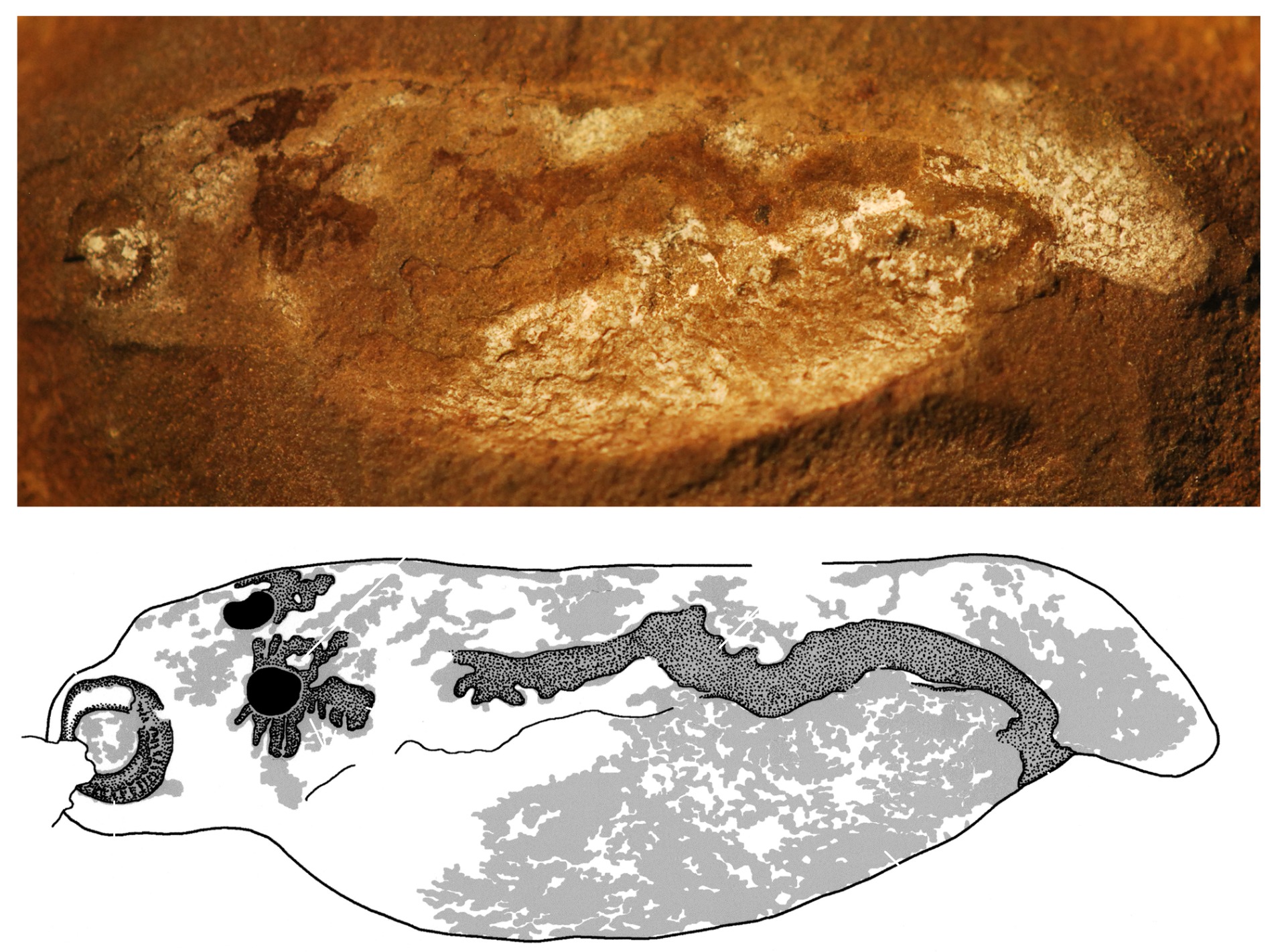

The hatchling of Priscomyzon associated with a yolk sac. Left: photograph of the specimen; Center: interpretive drawing of the specimen; Right: a Canadian quarter (25-cent coin) for size comparison.

Photograph and illustration by Tetsuto Miyashita

- Unlike ammocoetes, the fossilized larvae looked like their blood-sucking adult form. They had large eyes and a toothed sucker, which in modern lampreys only develop in the predatory adult.

The hatchling of Pipiscius associated with a yolk sac. Top: photograph; Bottom: interpretive drawing of the specimen.

From Miyashita et al. (2021)

- The fossilized larvae indicate that ancestral lampreys did not go through the blind, filter-feeding ammocoete stage during their growth.

Reconstruction of a hatchling individual of Priscomyzon. Note the prominent eyes, oral sucker, and small branchial region – in modern lampreys, these characteristics only develop across metamorphosis into the adult phase.

Illustration by Kristen Tietjen

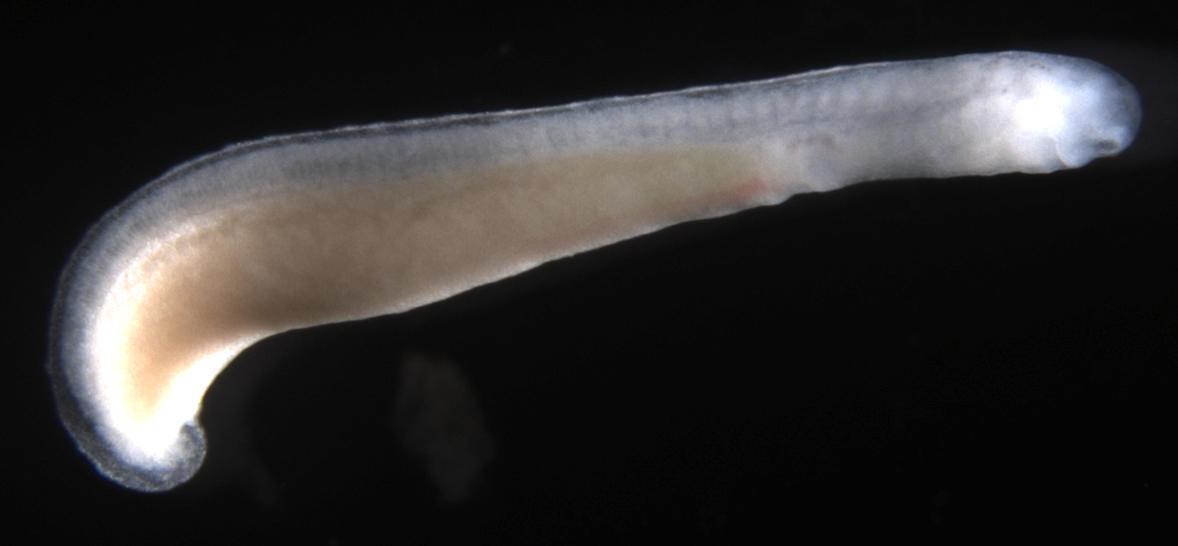

A hatchling of a modern lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). Unlike the larvae of Paleozoic stem lampreys, the modern lamprey larvae (ammocoetes) have rudimentary eye spots, a smooth oral hood, and a well-developed branchial region, and perform filter feeding.

Photograph by Tetsuto Miyashita

- Therefore, the ammocoete phase of a modern lamprey is not a relic of vertebrate ancestry, but a newly evolved feature, probably an adaptation during the Age of Dinosaurs to live in rivers and lakes where food supply was not as stable as in oceans.

- This means a change to the dogma presented in biology textbooks, which have placed ammocoetes as an ancestral model in vertebrate evolution.

Reconstruction of a representative early ostracoderm, Arandaspis. The vertebrate ancestor likely had a bony dermal skeleton (plates and scales) like these Ordovician forms.

Illustration by Franz Anthony

- Instead of larval lampreys, the new study places armored fossil fishes in the first links of a long chain of ancestors that eventually led to humans. These armoured fishes are called ostracoderms – or 'bony skins' for the scales and plates that covered their body – and were abundant in the ancient oceans 450 to 350 million years ago.

- Modern jawless fish like lampreys appear as primitive for lacking bones in their body (among other traits), but their seemingly ancestral anatomy is evolutionarily new. They lost the traits otherwise considered essential across vertebrates and evolved new ones (such as the ammocoete larval phase). This confused biologists for centuries about their antiquity.

Sucker for Life

This reconstruction of the Late Devonian estuarine lake in today's South Africa captures the life history of a stem lamprey Priscomyzon riniensis. Three individuals representing different ontogenetic stages take a shelter in the meadow of charophyte algae Octochara crassa. Clockwise from right: a yolk-sac-carrying hatchling tucked in the charophyte; a juvenile attached to the substrate in the foreground; and an adult looming over the other individuals and showing its feeding apparatus. In the background, a school of the coelacanth Selenichthys kowiensis swim by.

Art by Kristen Tietjen

— Additional Information —

Tetsuto Miyashita (back) and Robert Gess (front) discuss Priscomyzon

Michael Coates (back) and Robert Gess (front) at the Waterloo Farm roadcut, near Makhanda, South Africa (photography by Bruce Rubidge)

- Ammocoetes are so different from adult lampreys that they used to be considered separate species. It was only in the mid-19th century zoologists discovered that ammocoetes metamorphose into the blood-sucking lampreys.

- Modern lampreys live in freshwater; only in some species adults swim out to the sea. However, the fossil lampreys lived in a coastal environment (lagoons and estuaries). This suggests that the ammocoete stage was an adaptation to freshwater environment. Unlike in the oceans, the diversity of filter feeders is low in rivers and lakes, and prey abundance rises and falls unpredictably for predatory fish. So having a filter feeding larval stage (ammocoete) is a great way to "hedge bets" early in life until large prey items become available in a stable supply.

- These fossil lampreys were likely predatory as in the blood-sucking adult lampreys in modern rivers and lakes. However, the authors of the new study have different interpretations as to what the baby Priscomyzon ate. Tetsuto Miyashita thinks the larvae were predatory and their sucker operated underwater analogously with leeches, whereas Robert Gess thinks that the hatchlings may have had a different diet, perhaps grazing on algae like modern tadpoles.

- South Africa was near South Pole 360 million years ago when Priscomyzon lived. They probably coped with bright summers and dark winters like today's polar regions, but the climate was much warmer and ice was not permanent.

- Lampreys have long history of interaction with humans. It is a delicacy across Europe (e.g., Queen Elizabeth II's coronation and jubilee pies were baked with lamprey by the Royal Air Force; King Henry I died of food poisoning over a surfeit of lampreys), but also a beloved pet in the Roman Republic where senators would extend a great care to a pond full of them.

— Resources —

- Why ostracoderms are more primitive than lampreys or hagfish? Find out in a recent phylogeny of early vertebrates proposed by Miyashita and colleagues

- Lampreys are culturally important fish to the indigenous people across Northern Hemisphere. Watch The Lost Fish by Freshwater Illustrated.

- Learn more about the Waterloo Farm Lagerstätte (the locality of Priscomyzon)

- Coates Lab at the University of Chicago